Sections

- What is Vitamin D3?

- How does the Human Body Utilize Vitamin D3?

- Vitamin D3 Evidence Wheel (Interactive)

- Body Systems Influenced (Interactive)

- Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin D3 (Interactive)

- Summary

What is Vitamin D3?

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is a fat-soluble steroid hormone essential for maintaining overall health and wellness. Commonly known as “the sunshine vitamin,” vitamin D3 is naturally synthesized by the skin when exposed to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight. It can also be obtained through dietary sources such as fatty fish, egg yolks, and mushrooms, and through oral supplementation

Unlike other vitamins that must be obtained solely through diet, vitamin D3 is unique because your body can produce it endogenously when skin is exposed to sunlight, making it both a nutrient and a hormone. This dual nature distinguishes vitamin D3 from other essential vitamins and underscores its critical role in human physiology.

Vitamin D3 belongs to a class of organic compounds called secosteroids. These are steroids with one broken ring that are structurally similar to cholesterol, testosterone, and cortisol. Understanding its molecular composition is key to comprehending how vitamin D3 functions in your body.

The molecular architecture of vitamin D3 is remarkably sophisticated. The compound features a secosteroid backbone consisting of a steroid core with one ring opened, which confers vitamin D3 its unique biochemical properties.

The fat-soluble nature of vitamin D3 results from its predominantly hydrocarbon composition. This property allows it to be absorbed alongside dietary fats in the small intestine and transported through the bloodstream bound to vitamin D-binding protein. This structural feature distinguishes vitamin D3 from water-soluble vitamins like vitamin C, which require different absorption and transport mechanisms.

How does the Human Body Utilize Vitamin D3?

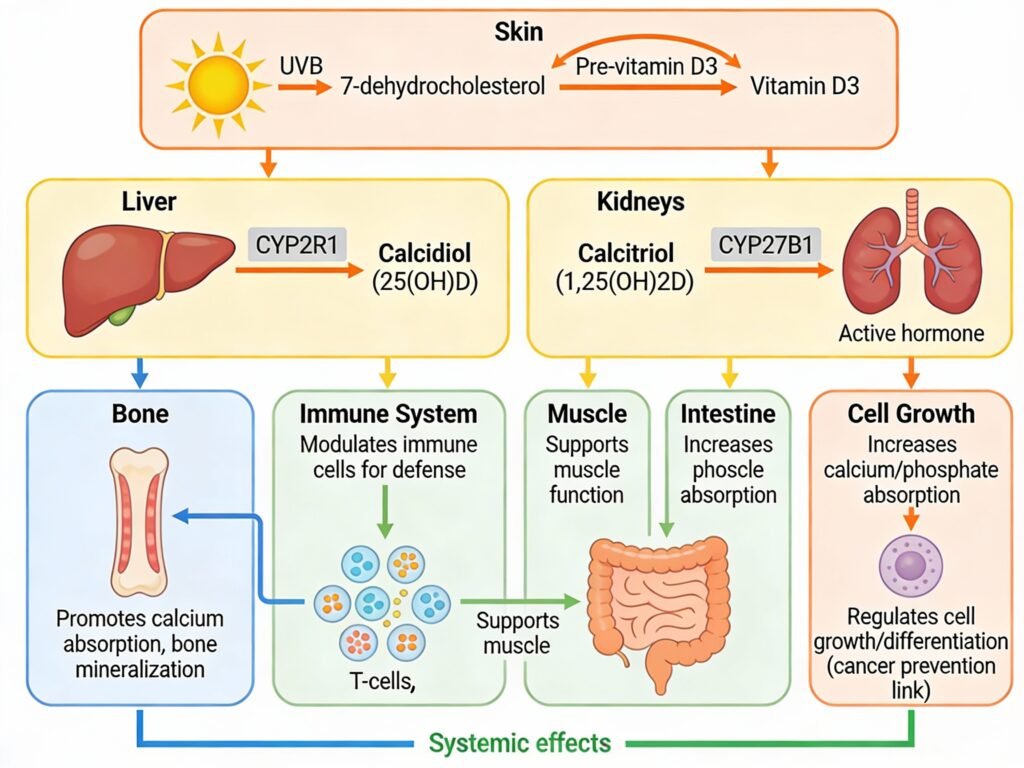

When you consume a vitamin D3 supplement orally, it travels through your digestive system largely unchanged until reaching the small intestine. Here, vitamin D3 is absorbed through passive diffusion and carrier-mediated transport involving intestinal membrane proteins, particularly cholesterol transporters. Consuming vitamin D3 with fat-containing meals enhances absorption, as dietary lipids facilitate movement of this fat-soluble molecule across the enterocyte brush-border membrane. Once absorbed, vitamin D3 enters the bloodstream and travels to the liver, where the enzyme CYP2R1 catalyzes the first critical hydroxylation step, converting cholecalciferol into 25-hydroxyvitamin D (calcidiol). Calcidiol is the major circulating form and serves as the most reliable biomarker for assessing vitamin D status.

The kidneys perform the second and most important activation step. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) directs the enzyme CYP27B1 (1-alpha-hydroxylase) to convert calcidiol into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), the most biologically active form of vitamin D. This active metabolite binds to the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) found throughout your body in bone, intestine, immune cells, brain, and cardiovascular tissues, triggering changes in gene expression that mediate vitamin D’s physiological effects. Additionally, the enzyme CYP24A1 inactivates vitamin D metabolites in the kidneys, skin, intestine, bone, and immune cells, converting them into less active forms that are subsequently excreted.

Individual responses to vitamin D3 supplementation vary significantly due to genetic polymorphisms in key metabolic enzymes and transport proteins. Variations in the CYP2R1, CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and GC genes (encoding vitamin D-binding protein) directly influence how efficiently your body converts dietary or supplemental vitamin D3 into its active form. Two individuals taking identical doses may achieve vastly different serum 25(OH)D concentrations due to differences in enzyme activity and DBP binding capacity. This genetic heterogeneity explains why some individuals are “responders” to vitamin D supplementation while others remain deficient despite adequate intake.

Vitamin D3 Evidence Wheel (Interactive)

Vitamin D3 has become one of the most extensively researched micronutrients in clinical medicine, with over 100 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining its effects on bone health and fractures, plus 37 dedicated infection trials. This massive scale of evidence demonstrates strong scientific consensus on its benefits, particularly for skeletal health and immune function. The research quality is robust for bone and immunity outcomes, though cardiovascular disease and cancer prevention findings remain mixed, with some studies showing benefit while others show no effect. Overall, the evidence strength is rated 7/10, reflecting both the compelling bone health data and the inconclusive results in other domains.

The benefits of vitamin D3 vary significantly by age and baseline vitamin D status. Older adults (65+) who are deficient experience a remarkable 16–30% reduction in fracture risk with supplementation, making it one of the most evidence-supported interventions for fall and fracture prevention in this population. In contrast, younger adults (18-64) show more modest benefits, primarily in muscle function and infection prevention for those with baseline levels below 40 nmol/L, with less convincing fracture data in this age group. The effect sizes are meaningful but moderate—supplementation reduces infection risk by approximately 12% (odds ratio 0.88) and fracture risk by 12–16% in elderly populations. Vitamin D3 is most beneficial for specific populations including older adults, individuals with baseline levels below 30 nmol/L, those with obesity, and people with darker skin tones who produce less vitamin D from sunlight exposure.

Genetic factors add another layer of complexity, with variants in the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and CYP27B1 genes moderately affecting how individuals metabolize and respond to supplementation; though these effects are not universal and most people benefit regardless of genetic background. Safety is excellent with great pharmacokinetics profile (see below). This comprehensive evidence profile, combining strong trial volume, documented benefits in target populations, excellent safety margins, and moderate genetic specificity, positions vitamin D3 as a well-validated supplement for bone health and immune support, particularly for older adults and deficient populations.

Body Systems Influenced (Interactive)

Vitamin D3 exerts the most significant influence on two critical systems: the skeletal system (25%) and the immune or lymphatic system (20%). The skeletal system represents vitamin D3’s most well-known function, where the nutrient facilitates calcium absorption in the small intestine and promotes bone mineralization, directly preventing osteoporosis and reducing fracture risk. The immune and lymphatic systems benefit enormously from vitamin D3 supplementation, as the vitamin D receptor is expressed on immune cells including T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages. Vitamin D3 regulates both innate and adaptive immune responses, modulates inflammatory cytokine production, and enhances antimicrobial peptide synthesis, making it essential for fighting infections and reducing autoimmune disease activity. The endocrine system (15%) also relies heavily on vitamin D3 for hormone regulation, including insulin secretion and parathyroid hormone control, while the integumentary (skin) and muscular systems (10% each) benefit from vitamin D3’s role in cell differentiation, muscle protein synthesis, and dermatological health

The remaining body systems also benefit significantly from adequate vitamin D3 levels. The cardiovascular system (7%) experiences improved heart function and reduced blood pressure through vitamin D3’s vasodilatory properties and anti-inflammatory effects, while the nervous system (5%) benefits from vitamin D3’s neuroprotective actions and its influence on dopamine and serotonin production. Respiratory function (4%) is supported through vitamin D3’s regulation of airway remodeling and immune tolerance in lung tissues, while the digestive system (3%) benefits from improved calcium absorption and reduced inflammation. Even the urinary system (1%) is influenced through vitamin D3’s regulation of renin production and blood pressure control.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and seasonal depression represent particularly compelling reasons to maintain optimal vitamin D3 levels year-round. During winter months and in northern latitudes where sunlight exposure diminishes significantly, vitamin D3 production in the skin decreases dramatically, leading to reduced circulating calcidiol levels. This deficiency directly impacts nervous system function, reducing serotonin and dopamine synthesis, key neurotransmitters responsible for mood regulation. Studies consistently show that individuals with vitamin D deficiency experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and seasonal mood disorders, while supplementation with vitamin D3 improves mood, reduces depressive symptoms, and helps prevent seasonal depression during winter months. For residents of Toronto and other northern regions with limited winter sunlight, maintaining vitamin D3 levels through supplementation is particularly critical for mental health and overall well-being.

Pharmacokinetics of Vitamin D3 (Interactive)

Pharmacokinetics (PK) studies are clinical research investigations that measure how your body absorbs, distributes, and eliminates vitamin D3 over time by tracking blood levels of 25(OH)D (calcidiol) and 1,25(OH)2D (calcitriol), the two major circulating forms of the vitamin. PK studies often use much higher single doses or different dosing schedules than recommended supplement bottles because clinical trials need to rapidly observe how the body processes vitamin D3, test for safety at extreme levels, measure individual absorption variations, and account for genetic differences that affect metabolism in controlled conditions that may not reflect real-world daily supplementation. Unlike the gradual daily dosing on supplement bottles which aims for steady long-term vitamin D3 levels, PK studies intentionally use concentrated doses to capture complete absorption and elimination data, understand peak blood concentrations, measure how quickly the body clears both metabolites, and identify potential toxicity thresholds. The ultimate goal of PK studies is to establish safe and effective dosing guidelines, determine optimal dose intervals for different populations, reveal how genetic variants influence individual responses to supplementation, and provide evidence-based recommendations that manufacturers and healthcare providers can use to help people achieve and maintain healthy vitamin D3 levels.

A landmark 2008 study by Ilahi et al., published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, investigated the pharmacokinetics of a single 100,000 IU oral dose of cholecalciferol in 30 healthy subjects with limited sun exposure. In this controlled clinical trial, researchers tracked serum calcidiol (25(OH)D) and calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D) concentrations over four months to understand how the body absorbs, metabolizes, and eliminates this large single dose of vitamin D3. The study demonstrated that a 100,000 IU dose of cholecalciferol is safe and effective, with serum calcidiol rising from a baseline of 27.1 ng/mL to a peak of 42.0 ng/mL, with individual peak values reaching as high as 64.2 ng/mL. As shown in the pharmacokinetic curve, vitamin D3 levels spike rapidly within the first 7 to 14 days, while the active metabolite calcitriol rises and peaks around 7 days before declining, while calcidiol maintains elevated concentrations throughout the four-month observation period.

A landmark 2008 study by Ilahi et al., published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, investigated the pharmacokinetics of a single 100,000 IU oral dose of cholecalciferol in 30 healthy subjects with limited sun exposure. In this controlled clinical trial, researchers tracked serum calcidiol (25(OH)D) and calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D) concentrations over four months to understand how the body absorbs, metabolizes, and eliminates this large single dose of vitamin D3. The study demonstrated that a 100,000 IU dose of cholecalciferol is safe and effective, with serum calcidiol rising from a baseline of 27.1 ng/mL to a peak of 42.0 ng/mL, with individual peak values reaching as high as 64.2 ng/mL. As shown in the pharmacokinetic curve, vitamin D3 levels spike rapidly within the first 7 to 14 days, while the active metabolite calcitriol rises and peaks around 7 days before declining, while calcidiol maintains elevated concentrations throughout the four-month observation period.

Based on the Ilahi study findings and subsequent pharmacokinetic research, vitamin D3 dosing recommendations have been optimized for different population needs. The data showed that a dosing interval of two months or less is optimal to maintain adequate serum 25(OH)D concentrations above 30 ng/mL, which is the threshold recommended by the Endocrine Society for overall health and disease prevention. For individuals who prefer frequent supplementation rather than large bolus doses, daily intake of 1,000 to 2,000 IU is considered the most efficient schedule because it provides more consistent serum levels and higher systemic exposure to calcidiol than weekly or bi-weekly dosing at equivalent cumulative doses. For those using higher-dose supplementation (such as 10,000 IU daily or 50,000 IU weekly), reaching the optimal 25(OH)D concentration of 30 to 48 ng/mL can be achieved within 4 to 8 weeks without safety concerns.

Summary of Vitamin D3

Individuals who would benefit most from vitamin D3 supplementation include older adults (age 50 and above), people living in northern latitudes with limited winter sunlight, pregnant and breastfeeding women, children and infants, and those with conditions affecting nutrient absorption such as celiac disease or cystic fibrosis. People with seasonal affective disorder, dark skin living in areas with minimal UV exposure, and individuals with pre-existing bone health concerns should also prioritize adequate vitamin D3 intake to maintain optimal serum levels and prevent deficiency-related complications.

Government health authorities and professional organizations worldwide agree on the critical importance of vitamin D3 supplementation. The National Institutes of Health and Food and Nutrition Board recommend that healthy adults aged 19 to 70 years obtain 600 IU daily, increasing to 800 IU for those over age 70, with a safe upper limit of 4,000 IU per day for most adults. Health Canada established that up to 2,500 IU daily is safe for non-prescription supplements for healthy children aged 9 and older, adolescents, and adults. The Endocrine Society recommends 1,500 to 2,000 IU daily for adults to achieve adequate serum vitamin D levels, exceeding the basic RDA for disease prevention and improved health outcomes.

Osteoporosis Canada advises all Canadians over age 50 to supplement with vitamin D3 since dietary sources alone are insufficient. The NHS in the United Kingdom recommends 10 micrograms (400 IU) daily for people age 1 and older, while Alberta Health Services recommends adults over 50 take 1,000 to 2,000 IU per day to achieve optimal vitamin D status. These consistent recommendations across North America, Europe, and internationally reflect the scientific consensus that vitamin D3 supplementation is essential for maintaining bone health, supporting immune function, promoting mental health, and preventing chronic disease across the lifespan.

References

- Ilahi M, Armas LAG, Heaney RP. Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):688-691. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.3.688

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D: a global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5(1):51-108. doi:10.4161/derm.24494

- Gominak SC, Nishino H. Vitamin D deficiency and sleep regulation: a review of the literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;30:7-16. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2015.11.005

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266-281. doi:10.1056/NEJMra070553

- Chowdhury R, Kunutsor S, Vitezova A, et al. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1903. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1903

- Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med. 2011;59(6):881-886. doi:10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755

- Wehr E, Pilz S, Schweighofer N, et al. Association of vitamin D status with serum androgen levels in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73(2):243-248. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03806.x

- Larson-Meyer DE, Willis KS. Vitamin D and athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(4):220-226. doi:10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181e7dd45

- Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666

- Grant WB, Holick MF. Benefits and requirements of vitamin D for optimal health: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10(2):94-111.

- Holick MF. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2062-2072. doi:10.1172/JCI29449

- Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117(4):503-511. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127

- Adorini L, Penna G. Control of autoimmune diseases by the vitamin D endocrine system. Nat Clin Pract Rheum. 2008;4(8):404-412. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0853

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(6):551-561. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.600

- Cranney A, Horsley T, O’Donnell S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007;158:1-235.

- Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(16):1730-1737. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730

- Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(23):1637-1642. doi:10.1056/NEJM199212033272305

- Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community. BMJ. 2003;326(7387):469. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469

- Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):670-676. doi:10.1056/NEJM199709043371003

- Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691. doi:10.1136/bmj.c3691

- Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):684-696. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222

- Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(5):1752-1755. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-1939

- Cauley JA, Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and health outcomes for postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative study. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927-2938. doi:10.1001/jama.296.24.2927

- Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(7):451-459. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj101

- Looker AC, Dawson-Hughes B, Calvo MS, Gunter EW, Sahyoun NR. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of adolescents and adults in two ethnic groups: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(4):863-869. doi:10.1093/ajcn/76.4.863

- Adams JS, Hewison M. Update in vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):471-478. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1773

- Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50-60. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0567

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline for the evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911-1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Heaney RP, Recker RR, Grote J, Horst RL, Armas LAG. Vitamin D(3) is more potent than vitamin D(2) in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):E447-E452. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2230

- Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(11):5387-5391. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0360

- Holick MF, Siris ES, Binkley N, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for North America. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):353-373. doi:10.4065/81.3.353

- Wang X, Morris JS, Formica V, et al. Serum vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(12):1365-1374. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr020

- Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):210-216. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004

- Vimaleswaran KS, Berry DJ, Lu C, et al. Causal relationship between obesity and vitamin D status: bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis of multiple cohorts. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001383. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001383

- Lips P. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2001;22(4):477-501. doi:10.1210/edrv.22.4.0437

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Shao A, Dawson-Hughes B, Hathcock J, Giovannucci E, Willett WC. Benefit-risk assessment of vitamin D supplementation. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:40-46. doi:10.3109/00365513.2012.681962

- Orwoll E, Riddle M, Prince M. Effects of vitamin D on falls, physical performance, and balance: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2328-2337. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02024.x

- Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Dick W, et al. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(2):343-351. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.343

- Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):6-18. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6

- PubMed Central, National Institutes of Health. Genetic variants influencing individual vitamin D status. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12389392/

- PubMed Central, National Institutes of Health. Intestinal absorption of vitamin D: a systematic review. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5573988/

- PubMed Central, National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D and the Central Nervous System. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9610817/

- PubMed Central, National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D: A Critical Regulator of Intestinal Physiology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jbm4.10554

- PubMed Central, National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D and bone health: from physiological function to clinical applications. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12490156/

- National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin D – Health Professional Fact Sheet. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

- Health Canada. Vitamin D. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/nutrients/vitamin-d.html

- National Health Service (NHS). Vitamin D. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/vitamin-d/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effect of Vitamin D on Blood Pressure and Hypertension. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/19_0307.htm