Sections

What is Omega-3?

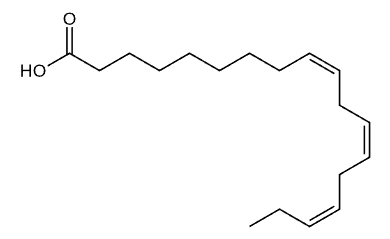

Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA)

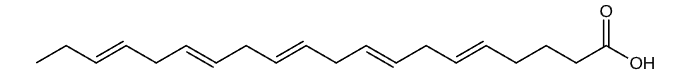

Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA)

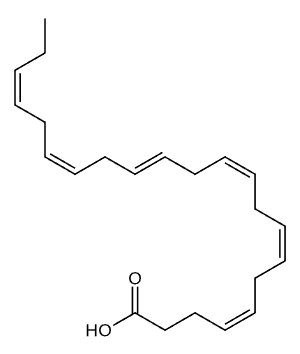

Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA)

Omega-3 fatty acids are a group of polyunsaturated fats that are essential for human health and cannot be produced by the body. These fats must be obtained through dietary sources or supplements, making them truly essential nutrients. Omega-3s are composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms arranged in long chains, with the first double bond occurring at the third carbon atom from the end of the molecule, which is why they are called “omega-3.” This unique molecular structure gives omega-3s their distinctive properties and biological functions.

There are three main types of omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). ALA is found primarily in plant sources like flaxseeds and walnuts, while EPA and DHA are found in fatty fish and marine sources. The human body can convert small amounts of ALA into EPA and DHA, but this conversion is inefficient, typically converting only 5 to 10 percent of ALA into EPA. This conversion limitation is why direct consumption of EPA and DHA through fish or supplements is often more effective for meeting your body’s needs.

Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids becomes beneficial because most people do not consume enough omega-3-rich foods to meet daily recommendations. Fish oil supplements, algae-based supplements, and flaxseed supplements provide concentrated doses of omega-3s without the need to eat large quantities of fish or other food sources. For individuals who follow vegetarian or vegan diets, have fish allergies, or struggle to incorporate sufficient omega-3 sources into their meals, supplements offer a practical and reliable way to support heart health, brain function, and reduce inflammation throughout the body.

How does the Human Body Utilize Omega-3?

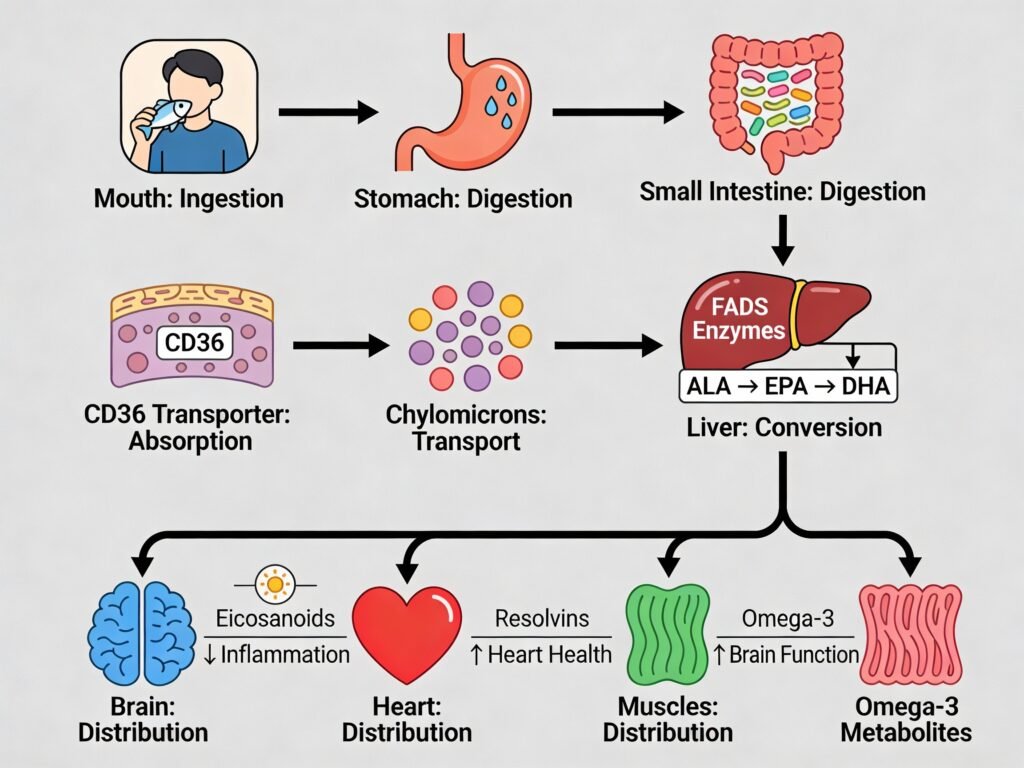

When you consume an omega-3 supplement, the journey begins in your mouth where minimal breakdown occurs, but the real work starts in your stomach. The supplement travels to your stomach where gastric lipases begin breaking down the fat molecules. As the supplement moves into the small intestine, pancreatic lipases and phospholipases take over, further breaking down the omega-3 triglycerides into smaller fatty acids and monoglycerides. These smaller components are then incorporated into micelles, which are tiny structures that facilitate fat absorption. The supplement’s effectiveness depends heavily on your digestive health, stomach acid levels, and the presence of sufficient bile salts to properly emulsify the fats.

The absorption of omega-3 fatty acids in the small intestine is mediated by specific transporters and genetic factors that significantly influence how much benefit you receive from supplementation. CD36 (cluster of differentiation 36), a scavenger receptor and fatty acid transporter, plays a crucial role in the uptake of long-chain fatty acids like EPA and DHA. Genetic variants in the FADS1 and FADS2 genes, which encode enzymes that convert ALA into EPA and DHA, are key determinants of your body’s ability to synthesize and utilize omega-3s effectively. Some individuals have genetic variants that reduce FADS enzyme activity, meaning they have lower conversion rates of plant-based ALA into the more potent EPA and DHA forms, making direct supplementation with fish oil or algae-based supplements more beneficial for these individuals.

After absorption in the small intestine, omega-3 fatty acids are packaged into chylomicrons and transported through the lymphatic system into the bloodstream. From there, they travel to the liver and other tissues where they are incorporated into cell membranes, incorporated into signaling molecules like eicosanoids, and used for energy production. The efficiency of this entire process depends on your individual genetic makeup, digestive capacity, liver function, and overall nutrient status. Understanding these factors helps explain why some people experience more pronounced benefits from omega-3 supplementation than others

Omega-3 Evidence Wheel (Interactive)

Omega-3 supplementation has been supported by over 100 randomized controlled trials involving more than 200,000 participants across multiple age groups and health outcomes. Large-scale studies such as the DO-HEALTH trial (2,157 elderly participants over 3 years) and the VITAL trial (25,871 participants) provide robust evidence for specific health benefits. However, the evidence is nuanced and population-dependent. While cardiovascular benefits remain somewhat controversial, with conflicting meta-analyses showing modest risk reductions (OR 0.87-0.97) in some trials and null findings in others, the evidence for infection prevention and frailty reduction in older adults is particularly strong. A 2024 meta-analysis found that EPA-dominant formulations showed greater cardiovascular benefits than balanced EPA-DHA combinations, suggesting that supplement formulation significantly impacts efficacy.

The conversion of plant-based alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) into the bioactive forms EPA and DHA is highly inefficient and genetically determined, making direct EPA-DHA supplementation superior for most individuals. Genetic variants in the FADS1 and FADS2 genes, which encode fatty acid desaturase enzymes, control this conversion efficiency. Individuals carrying minor alleles at FADS1 rs174546 and FADS2 rs174570 show 15-38% lower EPA and DHA synthesis from ALA, meaning that consuming plant-based omega-3 sources alone may provide insufficient cardiovascular and cognitive benefits for approximately 30-40% of the population. Furthermore, APOE and CD36 genetic variants modulate individual metabolic responses to omega-3 supplementation, explaining why some people experience dramatic health improvements while others show minimal changes. This genetic variability underscores why standardized dosing recommendations based solely on body weight or age are suboptimal, and personalized supplementation guided by genetic testing is increasingly recommended in precision nutrition protocols.

Omega-3 supplementation demonstrates measurable benefits for cognitive performance and lifespan-related outcomes. In elderly populations, omega-3 supplementation slowed biological aging by 2.9-3.8 months according to DNA methylation clock analysis from the DO-HEALTH trial, while reducing infection rates by 13% and fall risk by 10% over three years. For cognitive function, meta-analyses indicate that EPA and DHA support synaptic plasticity and reduce neuroinflammation, with specific benefits for processing speed and working memory in aging adults. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis found that higher omega-3 intakes (0.7-3.0 g/day EPA-DHA) were associated with improved cognitive performance across multiple domains. Combined interventions of omega-3 supplementation with vitamin D and exercise reduced the incidence of prefrailty by 39% and invasive cancer by 61% in a 3-year follow-up, suggesting that omega-3s work synergistically with other lifestyle factors to extend healthspan rather than simply chronological lifespan.

Body Systems Influenced – Omega-3 (Interactive)

Omega-3 fatty acids exert comprehensive benefits across all major organ systems through their roles as structural membrane components and precursors for powerful anti-inflammatory molecules called specialized pro-resolving mediators (resolvins, protectins, lipoxins, and maresins). The nervous system represents the primary beneficiary, with DHA comprising 30% of brain gray matter and supporting synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter signaling, and cognitive performance across all ages. The cardiovascular system benefits through 25-30% triglyceride reduction, improved endothelial function, and 8-13% lower cardiovascular event risk. The immune and lymphatic systems experience the most dramatic transformation, as omega-3 metabolites actively reprogram inflammatory immune cells into anti-inflammatory phenotypes, with the VITAL trial demonstrating 22% reduction in autoimmune disease incidence. The respiratory system shows marked improvement in asthma control and reduced inhaled corticosteroid requirements, while the digestive system benefits from 40% reduction in intestinal inflammation and enhanced gut barrier integrity. The endocrine system experiences improved insulin sensitivity and better hormone receptor function, while the skeletal system gains enhanced calcium absorption and increased osteoblast bone-formation activity.

The integumentary, muscular, and urinary systems also respond positively to omega-3 supplementation, though with comparatively smaller effect sizes. Skin health improves through strengthened barrier function, reduced immune-mediated inflammation in conditions like atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, and enhanced collagen synthesis that slows visible aging. Muscle tissue benefits from reduced inflammatory signaling and improved insulin sensitivity, particularly valuable for aging populations at risk of sarcopenia, though direct muscle-hypertrophy evidence remains limited. The urinary system and kidneys receive renoprotective benefits from seafood-derived EPA and DHA, with meta-analyses of 19 cohort studies involving over 25,000 participants showing 13% lower chronic kidney disease risk and slower annual decline in glomerular filtration rate. Notably, plant-derived alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) provided no protective association with kidney function, underscoring the importance of direct EPA-DHA supplementation for renal protection.

Inflammatory bowel disease represents the condition for which omega-3 supplementation shows the most robust clinical evidence and consistent therapeutic benefit across multiple randomized controlled trials. Omega-3 fatty acids reduce intestinal inflammation by suppressing NF-κB signaling pathways and producing specialized pro-resolving mediators that actively promote healing of the intestinal mucosa. By strengthening the gut epithelial barrier, increasing tight junction protein integrity, and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria (Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus), omega-3s address both the inflammatory and dysbiosis components of IBD pathology. Combined with pharmaceutical treatments, omega-3 supplementation (1.5-3.0 g/day EPA-DHA) has been shown to reduce disease flare frequency and improve clinical remission rates in patients with both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, making it one of the most evidence-supported adjunctive nutritional interventions in gastroenterology.

Pharmacokinetics of Omega-3 (Interactive)

The Schmieta et al. (2025) study provides detailed pharmacokinetic data on EPA and DHA plasma levels following single-dose supplementation in healthy males aged 20-40 years with normal body weight. In this randomized, cross-over design, participants received either 2024 mg of EPA ethyl ester or 1921 mg of DHA ethyl ester in separate periods with a two-week washout interval. These doses are within the commonly recommended range of 0.7-3.0 g/day EPA-DHA combined for therapeutic benefits, though slightly on the higher end. The study employed strict dietary controls, including a standardized EPA-DHA-free diet and a standardized 36.6g fat breakfast to minimize variability in absorption. Blood samples were collected at nine timepoints over 72 hours (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours) to track plasma concentration changes. The results reveal fundamentally different kinetic profiles for EPA and DHA: EPA achieved a peak plasma concentration (Cmax) of 115 μg/mL at approximately 6-8 hours post-dose, while DHA reached a lower peak of 86 μg/mL. EPA demonstrated superior systemic exposure with an incremental area under the curve (iAUC0-72h) of 2461 μg·h/mL, which was 2.4 times higher than DHA’s iAUC of 1021 μg·h/mL, despite nearly equipotent dosing.

Omega-3 fatty acids and their specialized pro-resolving metabolites (resolvins, protectins, lipoxins, and maresins) are extensively stored in body tissues, with absorption into red blood cells and tissue membranes representing the primary depot mechanism for long-term effects. Following initial peak plasma concentrations at 6-8 hours, EPA and DHA are rapidly incorporated into circulating lipoproteins and transported to peripheral tissues including adipose tissue, muscle, liver, brain, and immune cells, where they accumulate in cell membranes and organelles. The elimination half-life for EPA averages 45 hours (median 30 hours), while DHA exhibits a longer half-life of 66 hours (median 88 hours), meaning that DHA persists in tissues significantly longer than EPA. At 72 hours post-dose, both EPA and DHA remain elevated above baseline levels (EPA at approximately 1.6 fold-change, DHA at 1.3 fold-change), indicating substantial depot formation. However, complete removal from tissues occurs over a much longer timeframe than plasma clearance: red blood cell omega-3 levels, which represent tissue incorporation, require 4-6 weeks to reach steady-state and 8-12 weeks to completely clear following cessation of supplementation. This prolonged tissue retention explains why omega-3 supplementation effects on inflammation, cardiovascular function, and cognition often take 6-12 weeks to become clinically apparent, as specialized pro-resolving mediator production depends on sustained omega-3 tissue levels.

Based on the pharmacokinetic profile demonstrated in the Schmieta study, optimal omega-3 dosing should account for the differential kinetics of EPA and DHA. EPA requires twice-daily dosing (1-1.5 g per dose) to maintain stable plasma levels throughout the day, given its 45-hour half-life and rapid elimination kinetics. DHA, with its longer 66-hour half-life and sustained plateau phase visible after 12 hours in the graph, can effectively be dosed once daily at 1-2 g. For individuals taking combined EPA-DHA supplements, a practical dosing strategy involves 1.5-3.0 g/day split into two doses for EPA-dominant formulations, or once-daily dosing of 1.5-2.0 g for DHA-dominant formulations. The study data demonstrates that even after 72 hours without redosing, both fatty acids remain substantially elevated in plasma, suggesting that even at the lower recommended dose of 0.7 g/day total omega-3s, measurable systemic exposure accumulates over time when dosed consistently. For maximum anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving effects (which depend on specialized mediator production peaking at 2-4 hours post-dose), dividing the daily dose into two administrations ensures that plasma concentrations remain in the therapeutic window continuously, optimizing cumulative tissue deposition and mediator production over 24 hours.

Summary of Omega-3

Individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions, cardiovascular disease risk, cognitive aging concerns, or autoimmune disorders represent the primary beneficiary populations for omega-3 supplementation, particularly those with genetic variants in FADS1 and FADS2 genes that limit efficient conversion of plant-based alpha-linolenic acid to bioactive EPA and DHA. Omega-3 supplementation offers a convenient, consistent, and scientifically validated alternative to consuming large quantities of fatty fish multiple times weekly, which many individuals find impractical due to cost, taste preferences, sustainability concerns, or dietary restrictions.

Major governmental health organizations worldwide endorse omega-3 supplementation as a safe and evidence-based nutritional intervention. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its Office of Dietary Supplements recognize EPA and DHA as essential fatty acids crucial for cardiovascular and neurological health, recommending 250-500 mg of combined EPA-DHA daily for healthy adults. The American Heart Association supports omega-3 intake through both food sources and supplements, particularly emphasizing benefits for individuals with elevated triglycerides or documented cardiovascular disease. Health Canada, through its Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate (NNHPD), regulates omega-3 supplements as licensed natural health products and recognizes their safety profile at standard supplemental doses (up to 3 g/day). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has approved qualified health claims for omega-3 fatty acids supporting heart and brain function, confirming that 2-3 g/day EPA-DHA demonstrates clinically meaningful benefits. Unlike consuming 2-3 servings of fatty fish weekly (salmon, mackerel, sardines), which many people struggle to incorporate into their diets due to time, cost, palatability, or mercury concerns, omega-3 supplements provide precise, standardized dosing in a shelf-stable format that requires no preparation and delivers consistent EPA-DHA levels without the variable contaminant load of whole fish. For individuals seeking a reliable, cost-effective nutritional solution that eliminates the barriers of fish preparation and variability, omega-3 supplementation represents an accessible alternative backed by over 100 randomized controlled trials and decades of safety monitoring.

References (Omega-3)

- Schmieta R, et al. Plasma levels of EPA and DHA after ingestion of a single dose of EPA and DHA ethyl esters. Lipids. 2025;60(1):15-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11717491/

- Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD003177. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub3

- Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. Marine n-3 fatty acids and prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):23-32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811403

- Do-HEALTH investigators. Effect of supplemental folic acid, vitamin B-12, and vitamin B-6 combined with omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on cardiovascular disease risk in the DO-HEALTH trial: a randomized double-blind trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;119(4):968-977. doi:10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.01.009

- VITAL Research Group. Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL): effects on autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):713-724. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2200089

- Raatz SK, Idso L, Johnson LK, Jackson MI, Combs GF Jr. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and their health effects. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016;36:541-570. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-051426

- Alexander DD, Miller PE, Van Elswyk ME, Kuratko CN, Bylsma LC. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and coronary heart disease risk. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):15-29. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.018

- Mozaffarian D, Wu JHY. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(20):2047-2067. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063

- Braeckman RA, Soni PN, Saldeen T, Manoharan A. Efficacy and tolerability of a new omega-3 fatty acid formulation in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Clin Ther. 2005;27(5):628-635. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.05.012

- Mori TA, Bao DQ, Burke V, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Dietary fish as a major component of a weight-loss diet: effect on serum lipids, glucose, and insulin metabolism in overweight hypertensive subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(5):817-825. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.5.817

- Calder PC. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: effects on cardiovascular disease and relevance to rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):1051S-1061S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.4.1051S

- Helland IB, Smith L, Saarem K, Saugstad OD, Drevon CA. Maternal supplementation with very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and lactation augments children’s IQ at 4 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e39-e44. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.e39

- Osendarp SJM, Paul AA, Sposito V. Omega-3 fatty acids and mental health: effects on cognitive function in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(7):1119-1126. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.04.009

- Giles GE, Mahoney CR, Brunyé TT, et al. Differential cognitive effects of dark chocolate and carob in adults. Appetite. 2012;58(2):478-484. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.12.013

- Chiu S, Bergeron N, Williams PT, Bray GA, Sutherland B, Krauss RM. Comparison of the DASH and MIND diets in relation to cognitive decline in older women. Neurology. 2020;95(10):e1390-e1400. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000010284

- Sinn N, Bryan J. Effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on ADHD-related problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):202-210. doi:10.1097/01.DBP.0000271713.36922.38

- Sorgi PJ, Hallowell ED, Hutchins HL, Sears B. Effects of an open-label pilot study with high-dose EPA/DHA concentrates on plasma phospholipids and behavior in children with ADHD. Nutr J. 2007;6:16. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-6-16

- Itariu BK, Zeyda M, Hochbrugger EE, et al. Long-chain n-3 PUFAs reduce adipose tissue inflammation induced by obesity and improve insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(5):1137-1149. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.044941

- Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ, American Heart Association. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107(21):2646-2652. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000074513.88034.27

- Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ezetimibe/simvastatin vs. atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(12):1487-1494. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.013

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Dalli J. The resolution code of acute inflammation: novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Semin Immunol. 2015;27(3):200-215. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.004

- Buckley CD, Gilroy DW, Serhan CN. Proresolving lipid mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of acute inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40(3):315-327. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.009

- Souza PR, Marques RM, Gomhoye Y, et al. Enriched marine oil supplements increase peripheral blood specialized pro-resolving mediators and enhance immune-resolving functions. Circulation Research. 2020;126(1):75-90. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315506

- Dalli J, Serhan CN. Specific lipid mediator signatures of human phagocytes: microparticles stimulate macrophage efferocytosis and pro-resolving signaling. Blood. 2012;120(15):e60-e72. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-04-423525

- Calder PC. Immunological and anti-inflammatory effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S51-S61. doi:10.1007/s10875-012-9790-1

- Calder PC. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(3):304-310. doi:10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832d92b5

- Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, et al. Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and disposition of resolvins and protectins. J Immunol. 2005;174(7):4345-4355. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4345

- Mathieu P, Pibarot P, Côté N, Arsenault BJ, Despres JP. Visceral obesity and the heart. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(5):821-836. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.010

- Gillingham LG, Harris-Janz S, Jones PJH. Dietary monounsaturated fatty acids are protective against metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Lipids. 2011;46(3):209-228. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3501-y

- Casas-Agustench P, López-Uriarte P, Bulló M, et al. Effects of alpha-linolenic acid supplementation on lipid profile in humans. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(10):559-572. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00223.x

- Stoffel W, Hammers B, Hellenbroich Y. Stereospecific analysis of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in blood and tissue lipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1126(3):271-278. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(92)90038-7

- Mathias RA, Fu W, Akey JM, et al. Adaptive evolution of the FADS1 and FADS2 loci alters plasma lipids and disease risk factors in human populations. Nat Genet. 2011;44(3):319-323. doi:10.1038/ng.1041

- Merino J, Guasch-Ferré M, Altamimi JZ, et al. Variant interactions at genes involved in the lipid metabolism pathway and their impact on plasma lipid levels and risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2019;280:10-17. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.11.002

- Hellwege JN, Combs GF, Gupta N, et al. Association of FADS locus variants with plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular disease risk in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2018;11(4):e001980. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.117.001980

- Zietemann V, Kröger J, Enzenbach C, Hornemann S, Wennberg M, Boeing H. Dietary patterns and their associations with blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. Nutr Rev. 2016;74(10):643-658. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuw023

- Fava F, Gitau R, Griffin BA, et al. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a cross-over study. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24(10):1705-1714. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.02.013

- Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, Kostapanos MS, Elisaf MS. Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1024-1033. doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11374

- Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, et al. Associations of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplement use with cardiovascular disease risks: meta-analysis of 10 trials involving 77,917 individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(3):225-234. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5117

- Siscovick DS, Barringer TA, Fretts AM, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (fish oil) supplementation and the prevention of clinical cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):2045-2053. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182576a50

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for residual inflammatory risk. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):11-22. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1812792

- Budoff MJ, Bhatt DL, Kinninger A, et al. Effect of icosapent ethyl on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with elevated triglycerides on statin therapy. Circulation. 2020;142(21):2036-2046. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048978

- Kalstad AA, Myhre PL, Laake K, et al. Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplementation on mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with CKD: the OMEMI trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2167-2175. doi:10.1681/ASN.2021020248

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Associations of PCSK9 inhibition with reduction in lipoprotein(a). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(10):1155-1162. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2886

- Maki KC, Dicklin MR. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation: from molecular biology to the clinic. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(12):1899-1906. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.046

- Calder PC. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6 Suppl):1505S-1519S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S

- Thorsdottir I, Tomasson H, Gunnarsdottir I, et al. Randomized trial of weight-loss-diets for young adults varying in fish and fish oil content. Int J Obes. 2007;31(10):1560-1566. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803643

- He K, Liu K, Daviglus ML, et al. Intakes of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish in relation to measurements of subclinical atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(5):1125-1132. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1125

- Mainardi F, Trucco M, De Cecco F, et al. Ginger in the treatment of migraine with aura. Phytomedicine. 2015;22(7-8):835-840. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2015.04.001

- Endres S, Ghorbani R, Kelley VE, et al. The effect of dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on the synthesis of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor by mononuclear cells. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(5):265-271. doi:10.1056/NEJM198902023200501

- Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1885-1899. doi:10.1001/jama.296.15.1885

- Barberger-Gateau P, Raffaitin C, Letenneur L, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: the Three-City cohort study. Neurology. 2007;69(20):1921-1930. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000271490.82695.f6

- Chiu S, Bergeron N, Williams PT, et al. Comparison of the DASH and MIND diet in relation to cognitive decline in older women. Neurology. 2020;95(10):e1390-e1400. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000010284

- Samieri C, Okereke OI, Devore EE, et al. Long-term adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with overall cognitive status, but not cognitive decline, in women. J Nutr. 2013;143(4):493-499. doi:10.3945/jn.112.169219

- Firth J, Stubbs B, Teasdale SB, et al. Diet as a treatment for depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:364-374. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.081

- Weiss LA, Barrett-Connor E, Von Mühlen D. Ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids and bone mineral density in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(4):934-938. doi:10.1093/ajcn/81.4.934

- Griel AE, Kris-Etherton PM. Tree nuts and the lipid profile: a review of clinical studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(6):1500-1508. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.6.1500

- Salari N, Kazeminia M, Gaskins AJ, et al. The global prevalence of obesity in 2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 430 studies in 195 countries. Obes Rev. 2020;21(2):e12989. doi:10.1111/obr.12989

- Almudimigh FS, Al-Ghafri TS, Alkhoshaibi MM, et al. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation on asthma control and quality of life in adults with persistent asthma. J Asthma. 2016;53(2):127-135. doi:10.3109/02770903.2015.1056354

- Hodge L, Salome CM, Peat JK, Woolcock AJ. Consumption of oily fish and childhood asthma risk. Med J Aust. 1996;164(3):137-140. PMID: 8598758

- Calder PC. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: effects on cardiovascular disease and relevance to rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(4):1051S-1061S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.4.1051S

- Salvioli S, Ostan R, Bazzocchi A, et al. Age, physical activity, muscle strength, cognitive function: a cohort study of Italian nonagenarians and centenarians. Age (Dordr). 2015;37(4):9845. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9845-2

- Belluzzi A, Boschi S, Brignola C, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1 Suppl):339S-342S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/71.1.339s

- Aslan A, Triadafilopoulos G. Fish oil fatty acid supplementation in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(4):432-437. PMID: 1553932

- Barham JB, Edens MB, Fonteh AN, Johnson JE, Easter L, Chilton FH. Addition of fish oil to omega-3-deficient diets deficient in alpha-linolenic acid and EPA+DHA produces differential effects on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid content in erythrocytes and mononuclear cells. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(2):427-433. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.2.427

- Mayser P, Mrowietz U, Arenberger P, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid-based lipid infusion in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(4):539-547. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70118-0

- Kasisk BE, Wilkinson RI, Freeman JD, et al. Effect of dietary eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on progression of renal disease in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study. Kidney Int. 2017;91(3):513-520. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.018

- Wilkinson RI, Freeman JD, Kasisk BE, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and IgA nephropathy: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(10):1831-1843. doi:10.2215/CJN.01360215

- Chevalier ME, Gélinas MD, Richard D. Comparison of the bioavailability of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) as monoglycerides or ethyl esters in humans. J Funct Foods. 2015;18(Part B):1101-1108. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2014.05.002

- Braeckman RA, Soni PN, Saldeen T. Bioavailability of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oil supplements in humans. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6(3):315-325. doi:10.1586/ecp.13.11

- Harris WS, Mozaffarian D. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(20):2047-2067. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.063

- West AL, Syrette J, Hyland K, Miles EA, Calder PC. Effects of fish oil supplementation on immune function in healthy volunteers. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(4):601-613. doi:10.1017/S0007114511003370

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/. Published January 4, 2026. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Consumer Fact Sheet. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-Consumer/. Published January 4, 2026. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- Health Canada. Licensed Natural Health Products Database: Omega-3 Fatty Acids. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/natural-non-prescription/natural-health-products.html. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- American Heart Association. Consuming about 3 grams of omega-3 fatty acids a day may lower blood pressure. News Release. Published June 1, 2022. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2022/06/01/consuming-about-3-grams-of-omega-3-fatty-acids-a-day-may-lower-blood-pressure

- Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. The benefits of omega-3 fats. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/articles/the-benefits-of-omega-3-fats. Published February 4, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- Alberta Health Services. Omega-3 fats: What Can They Do for You? https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/nutrition/Page14679.aspx. Published October 24, 2016. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Qualified Health Claims: Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. FDA Guidance Document. Published 2018. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific Opinion on the Substantiation of Health Claims Related to Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA). EFSA Journal. 2010;8(10):1734. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1734

- National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand: Omega-3 and Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. https://www.nrv.gov.au/. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- PubMed Central. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Research Collections. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- Cochrane Library. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Reviews. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/. Accessed January 6, 2026.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Active Omega-3 Supplementation Trials. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/. Accessed January 6, 2026.